22. Halloween (2018)

Like The Force Awakens, David Gordon's Green's reboot of the Halloween franchise is heavy on nostalgia. It is competently directed and, unlike many of the earlier sequels, its central story is, at least, character driven. With that said, it is terribly unfocused and tonally inconsistent. It also suffers from an excess of meta-commentary surrounding the character of Micheal Myers. Despite these issues it remains one of the better sequels, though it feels completely unnecessary and adds nothing of value to the original.

6/10

23. Halloween Kills (2021)If the 2018 reboot felt unnecessary this sequel was even more so. At the very least the former brought the series to a semi-satisfying conclusion. Here, once again, Myers' death is retconned in an incredibly contrived fashion and the rest of the film struggles to justify its own existence. The writers are trying to say something about mob mentality and collective trauma, but its all so muddled and confusing that it never really lands. What's worse, these admittedly weighty themes are dealt with amidst some of the most unintentionally (I think) hilarious scenes I've ever seen in a slasher film (and that's saying something).

4.8/10

24. Halloween Ends (2022)It would seem that the series had no where to go but up after Halloween Kills. This, the final chapter in Green's reboot trilogy is, at the very least, better then its immediate predecessor. Its also, certainly, one of the more daring of the Halloween sequels. Like Rob Zombie's Halloween II it attempts to explore mental trauma and mental disease. However, unlike Zombie, Green is not willing to let Micheal take a back seat, and the film devolves into a contrived final showdown between Micheal and Laurie that is neither as satisfying as what the 2018 film had to offer nor as audacious as Zombie's more interesting (if equally flawed) pair of films.

5.8/10

25. The Babadook (2014)Anchored by a strong central performance from Essie Davis, The Babadook relies on symbolism to tell its story. This is both the directors greatest strength and the films greatest liability, as the subtext often overwhelms the text of the story. Nonetheless, the film remains an interesting, if somewhat heavy-handed exploration of grief and anger and an impressive debut for Australian director Jennifer Kent.

8.4/10

26. The Exorcist (1973)

This year I decided to watch the theatrical cut of Friedkin's masterpiece, and I was pleasantly surprised to find some of the more over-the-top antics "removed." Regardless, I found the film improved with a second viewing. Horror, especially supernatural horror, is most effective when the evil is suggested rather than seen, and Friedkin is a master at this. The ending, though theologically ambiguous at first glance, seems to me a powerful testament to God's ability to "write straight with crooked lines," to bring good out of terrible evil. Hence Fr. Karras, who is in danger of losing his faith, finds redemption in the most unlikeliest of ways, and Regan's seemingly meaningless suffering is imbued with a salvific purpose.

8.8/10

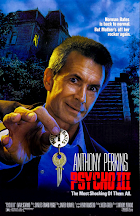

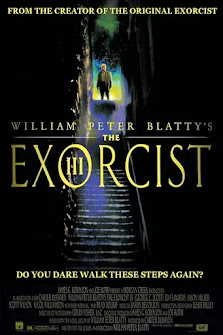

27. The Exorcist III (1990)A better film then it has any right to be, the third Exorcist film sees writer/producer William Peter Blatty step behind the camera to set the series back on course after the disaster that was Exorcist II (which, to be fair, I have never seen). Blatty lacks Friedkin's visual flair, and, if the original is at its best in its most silent moments, Exorcist III works best when people are having conversations. Fortunately, it's a very dialogue driven film, focused on Lieutenant Kinderman's (George C. Scott replacing the deceased Lee J. Cobb) interrogation of a man who appears to be the long-departed Karras. The film plays fast and loose with continuity. Kinderman and Karras, who barely speak to each other in the original film, are portrayed here as having been good friends. It also plays fast and loose with its theology, both morally and cosmologically.

7.4/10

28. Clue (1985)To take a break from all the doom and gloom, we watched this film with our younger siblings. Clue is a wonderful little screwball comedy, somehow managing to capture the spirit of the boardgame that inspired it, while retaining a spark of originality. The manic energy, which mounts as the film goes on, is largely aided by Tim Curry's hilarious turn as the butler, Wadsworth, but he is ably supported by an all around great cast and a sharp script from writer/director Jonathan Lynn. Its not a horror film but it features enough spooky/macabre imagery to qualify for wholesome seasonal viewing.

8.2/10

_theatrical_poster.jpg)